This post is part of the series on my work on JUnit supported by the Sovereign Tech Fund (STF). Please refer to the initial post for context and a list of all posts.

A major goal of the Sovereign Tech Fund’s investment is to help projects become more sustainable and decrease their truck factor. For JUnit, one activity in desperate need of improvement in this area was performing a release. Prior to this milestone, all JUnit releases of the past years had been performed from my local computer.

Artifacts were uploaded to Maven Central via Sonatype’s OSSRH infrastructure from my machine. Documentation and sample projects were also updated by a local build running on my machine. In total, the release checklist had 24 steps that I would perform manually for every release. Whenever I told people this, I was afraid they would gasp. However, releases of JUnit were not that frequent and it never felt important enough to spend the little time I had on release automation.

While that may sound reasonable, doing releases this way was also a bad idea from a security perspective. A malicious actor would only have to compromise my machine (or me) in order to pull of a supply chain attack. A manipulated JUnit jar would soon find its way to a large portion of the Java ecosystem. While usually not part of any production system, JUnit runs during the build and could be used to manipulate production code. Therefore, I jumped at the opportunity to rectify this deficiency and proposed a milestone to the STF for verifying the release and automating the majority of it.

One additional reason for doing releases locally was that Maven Central requires artifacts to be signed with a PGP key. Doing the release on a CI system therefore would mean trusting that system with my private key. In my book, that’s a bad idea as well. Even if the CI system might only store the private key temporarily, it could have been compromised, have some kind of data leak etc. Thus, I decided to keep that step local. However, since JUnit’s artifacts are completely reproducible, I would keep building and signing them locally, but rebuild them on a CI system. Thereby, the release process would verify the integrity of the binaries and rule out that they had been tampered with.

Thus, I decided to keep the first part of the release process local:

- Create a release branch

- Change to release version

- Change release date in README and release notes

- Build and deploy release artifacts to Sonatype staging repository

- Create a tag for the release

- Change back to snapshot version

- Push to GitHub

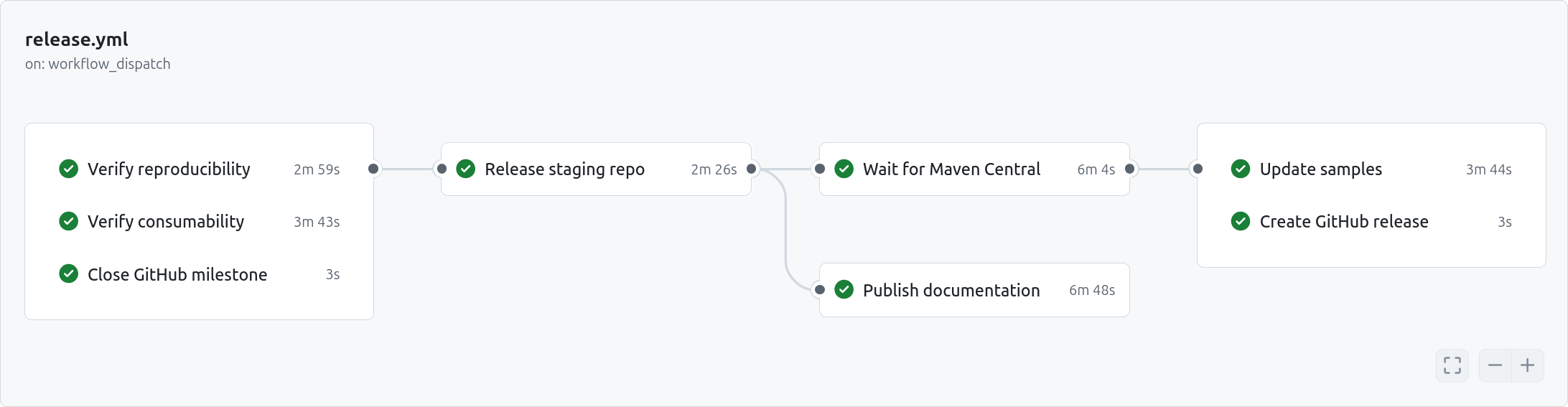

The remainder of the release is now performed by triggering a GitHub Actions workflow:

The most important job in the above workflow is “Verify reproducibility”. It checks out the Git tag, rebuilds all binaries, and verifies that they are identical to the ones uploaded to the staging repository. This step verifies not only their reproducibility but also rules out that they have been compromised by my local build.

The “Verify consumability” job updates all sample projects to consume the artifacts from the staging repository and builds them. Once the first phase is done, the staging repository is released. While waiting for the release artifacts to be synced to Maven Central, the documentation is published. Once the artifacts are indeed available on Maven Central, the sample projects are updated again but without the previous configuration that caused them to consume artifacts from the staging repository. Finally, a GitHub release is created.

Since I introduced this workflow in January, it has already been run 7 times taking between 15 and 26 minutes. It has definitely made releasing less stressful and I’m really happy how it turned out.